Day One Stuff

W&S is a weekly newsletter about reading, writing, and publishing by author Colin Wright.

Day One Stuff

I’ve been writing and publishing books professionally since 2010. I make a significant portion of my total living from book royalties, and I even ran a small, indie press with some fellow authors for a handful of years.

But I’ve always self-published, and that’s worked well enough that I didn’t see any reason to jump into the traditional publishing world until now.

Why now?

I’ve always wanted to dip my toes into the conventions and procedures of the traditional publishing establishment, if and when the opportunity presented itself. I realized about a year ago that this is an ideal time to do so, as I have the right project to shop around, and I have my life set up so that there’s time in which to write a whole lot while also navigating the querying process.

I’d also like to spend more time writing fiction (most of my published work has been nonfiction up till this point), and I want to have a collaborator as I work to refine my voice and the stories I’m telling, which is something the right agent and editor can offer.

All of this is strange, though, as again—I’ve been doing this a long, long time.

I’ve been making a living from my writing even longer than I’ve been publishing books, but now I’m back to Day One stuff: everything is new and I have little to no credibility in the space I’d like to enter.

After spending most of 2025 on this, I’m finally at a point with this traditional publishing thing where I know some stuff, I can chart actual progress, and I have a sense of likely timing, of next-step responsibilities, and of Plan Bs, Cs, and Ds, should my core goals not pan out.

So it’s odd, feeling like a beginner again after so many years of the opposite.

It’s also good, though, as it means I have a chance to grow, and maybe rapidly.

Some Writing (& Such) Links

The King of Blurbs

My understanding is that blurbing can become a key component of a traditionally published author’s life, and it’s interesting to hear about these sorts of blurbing extremes.

From the piece:

Back in 2008, King wrote about his blurb habit in Entertainment Weekly, saying, “I’ve lent my name to perhaps a hundred books.” He admits that his first blurb was for a book he didn’t especially like, but claims that since then “I’ve done it only for books I honestly loved.”

The year he wrote that article, a Seattle librarian noted that King described more than one book as his favorite of the year, which obviously can’t be possible. And over on Goodreads someone has attempted to crowdsource a list of all the books King has recommended in blurbs or other reviews, which seems an overwhelming challenge.

So yes, Stephen King blurbs a lot of books.

But as much as I like puns, in this case, I actually wasn’t talking about Stephen King. I meant “king” in the sense of a person who is at the top in a category. Because it turns out that, among literati, Stephen King is not the King of Blurbs. Another candidate might be A.J. Jacobs, an author who describes himself as having a “blurbing problem.” But he doesn’t get the title of Blurb King either.

That crown belongs to a guy named Gary Shteyngart.

New TV Novels

A solid and complex look at the (increasingly tight) relationship between novels and TV shows.

From the piece:

Novels are better than television, but the surest way to make money from novels is to write with television in mind.

Shortly after TV began to think of itself as novelistic, TV studios started turning their attention toward actual novels. Television had mostly left literature alone before the prestige revolution — fewer than ten TV shows produced annually prior to 2000 were based on existing literary properties — and most of the books that did get adapted (Little House on the Prairie, Pride and Prejudice) had been published decades before they found their way to the small screen. By 2020, with streaming platforms and premium cable channels churning out near-instantaneous adaptations of some of this century’s most critically and commercially successful novels, new book-to-TV projects were appearing to the tune of eighty or ninety a year. These adaptations offer a neat, if partial, index of trends in scripted television throughout the boom years preceding the 2023 WGA strike. Some became residually prestige “must-see” entertainment (Game of Thrones). Some were the slickly made products of streamers’ short-lived interest in auteurs (The Underground Railroad), while some confirmed HBO’s continued dominance over an upper-middlebrow market that Amazon and Netflix briefly tried to corner (The Sympathizer, Station Eleven, My Brilliant Friend). Some were pandemic-era discourse machines that finally got homebound viewers to shell out for Hulu (Normal People, The Handmaid’s Tale). Some had “little” in the title and Reese Witherspoon in the cast (Little Fires Everywhere, Big Little Lies). Most became inconsequential puff that nobody, even the original novels’ most dedicated readers, seemed to pay much attention to.

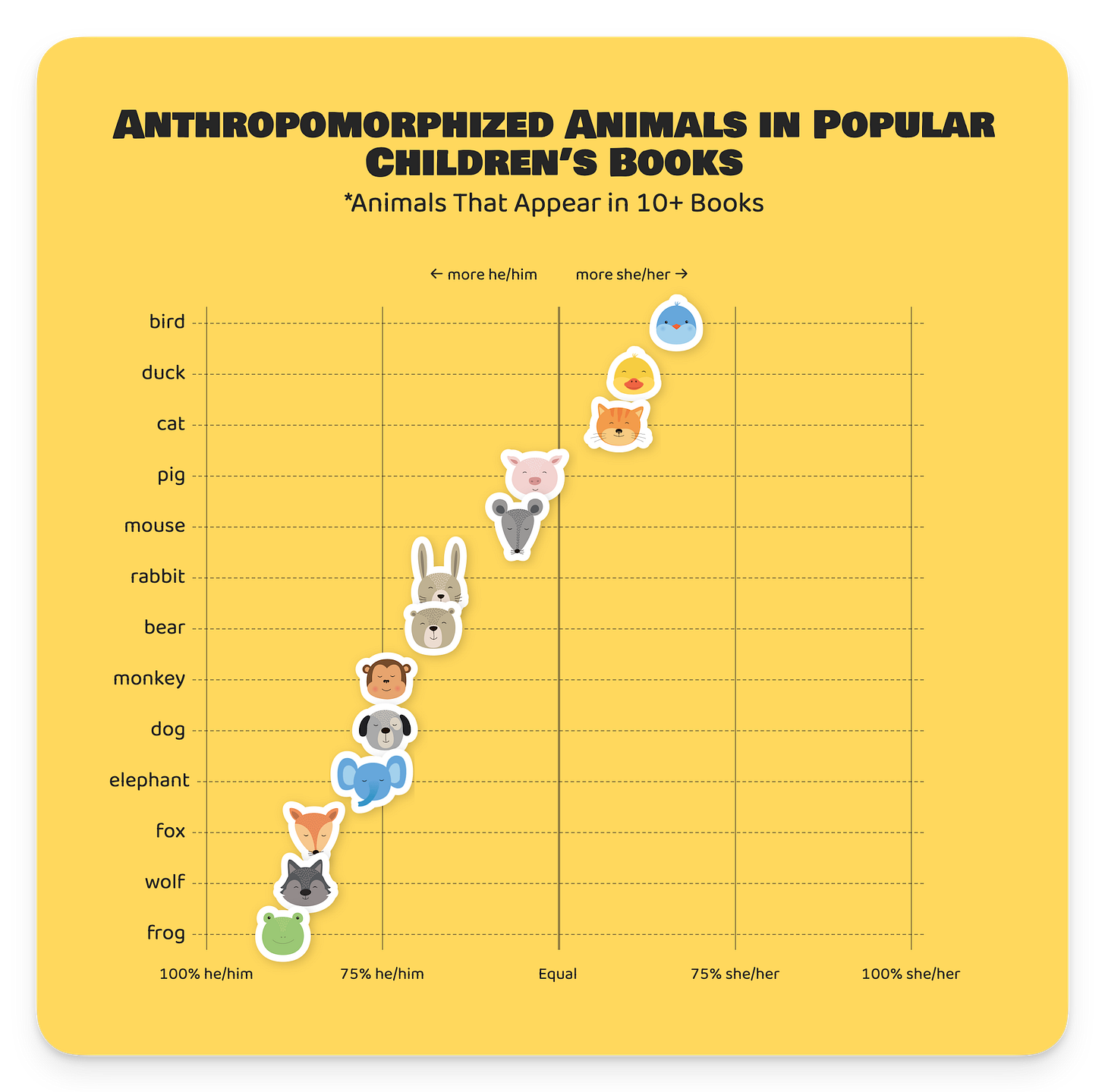

Bears Will Be Boys

One of a million gems over at The Pudding, this one on the genders of different animals in children’s books.

From the piece:

When I spend time with kids, I become hyperconscious of my word choices. “Look at Mr. Frog in the pond. Doesn’t he look grumpy?” Why did I say Mr. Frog? Why did I say he?

Where do these gendered presumptions even come from, and how pervasive are they? Is it common to assume that a frog is a “he?” What about a bear, or a bird, or a cat, or a pig?

I wanted to know: Which animals do we gender, and why?

Say Hello

New here? Hit reply and tell me something about what you’re writing, what you’re writing, reading, and/or about yourself!

I respond to every message I receive and would love to hear from you :)

Prefer stamps and paper? Send a letter, postcard, or some other physical communication to: Colin Wright, PO Box 11442, Milwaukee, WI 53211, USA

Or hit me up via other methods: Instagram, Threads, Twitter (ugh, but okay), or Facebook.