Querying

W&S is a weekly newsletter about reading, writing, and publishing by author Colin Wright.

Querying

For those who don’t know, if you want to publish a book in the US via a big publisher (as opposed to indie publishing or going with a smaller press), you will usually need an agent to serve as an intermediary between you and the publisher.

So for traditional publishing it’s:

Author → Agent → Publisher → Reader

vs. indie publishing:

Author → Intermediary platform (like Amazon KDP) → Reader

That agent only gets paid when you get paid (taking 15% of what you make from the book, though that can be higher with some types of sales, like foreign rights), and often they’ll work with you to refine the manuscript before then shopping it around to publishers they think might be interested (at which point there’s even more editing).

So just to get started—if you decide to take the traditional publishing path—you have to find yourself an agent. And though this can be relatively easy if you’re famous or already a well-known author, it’s usually pretty ponderous and uncertain, as the primary means through which authors get agents is via the query letter: a one-sheet introduction in which you provide details about your book, explain where it would fit in the market, and share a bit about yourself.

The general consensus (which isn’t universal, as with everything in this industry) is that the letter should ideally be short, capped at somewhere between 350 and 500 words (some agents are vehement about as short as possible, others are fine with whatever will fit on a single sheet of paper as long as it’s skimmable), and that it should have something like 4-5 paragraphs.

Optimally, one of those paragraphs should introduce your book’s concept, protagonist, and inciting incident, while the next should gesture at other things that happen throughout the narrative, fleshing out the story without becoming too verbose. Paragraph three should contain the book’s metadata, like the number of words, genre, and comps (comparative titles: “It’s like (successful book) crossed with (other successful book), but with the voice of (maybe another book, maybe a film, video game, etc”), and the final paragraph should tell the agent something about the author, including writing-related accolades and experience.

Agent preferences seem to vary a fair bit on query letter structure (some agents recommend putting your metadata up top, for instance), and advice on comps is all over the place, though almost always suggests avoiding genre-breaking hits like Harry Potter and The Hunger Games, while also trying to stick with books from the past 3-5 years.

Do enough research, though, and you’ll find at least one agent who disagrees with something all the other agents prefer, so there’s a lot of case-by-case customization involved, even after you write and refine what feels like a generally solid query letter.

“Querying hell”—the process of sending your query letter (and synopsis, biography, and other info) to agents—is notorious among authors, because for many people this is a multi-month to multi-year process, during which they systematically send their bundle of materials out to strangers who in some ways hold the author’s future and fortune in their hands, and who are (based on at times opaque metrics) judging the quality and/or validity of that work.

Even the most celebrated, successful authors have piles of rejections from agents who didn’t think their book was particularly good or sellable (or a good fit for the publishers with whom they had tight relationships).

Coping with all that judgement—paired with the desire to read rejection letter tea leaves for useful feedback—can be a part-time job all unto itself. Some responses will be positive (if still a rejection), some will be a mix of practical, corrective advice and compliments, but most will be form letters: boilerplate telling the author little beyond “this isn’t what I’m looking for right now, thanks.”

There’s a vulnerability hangover component to this, too, I think. The mere act of sending something so personal, something that’s taken so much time and energy to develop and hone, something that’s a reflection of the author’s creative capacity and ability to both cognate and communicate, can be exhausting. Putting oneself out there is exposing, and asking for feedback—for criticism!—while thus exposed is a simultaneously optimistic and masochistic act.

I started querying my novel, Yore, the other day. I’ve been working on the query package for what feels like ages, but which in reality was only a month or so.

Even preparing for the query process can feel vaguely punitive, like an unnecessary, labor-intensive, emotionally rent-seeking wall between author and agent. It’s work that stands between everyone involved and the work they should actually be doing!

The more I learn about how this aspect of the industry functions, though, the more sense it makes. It’s a brutal sort of sense, but I think I get it now.

Agents’ inboxes overflow with messages, and without some kind of formalized process for getting them the information they need (what the book is about, where it would be shelved in bookstores and how they might pitch it to publishers, and who the author is), they’d only realistically be able to weed through a small fraction of what they’re sent.

Querying is an imperfect and often tedious process, but it’s also arguably better than the alternative, both in the sense that agents don’t have to scramble so much to see if the books being shared are good fits for them (it’s all right there in the letter), and in the sense that more authors stand a chance of actually having their work seen by agents (because they can make it through more consistently structure queries than random selections of book-related bits and bobs).

That’s what I keep telling myself, anyway. There’s a non-zero chance my opinion will swing back toward “this is nonsense and I hate it” as I spend more time in the trenches, and as the rejection letters pile up.

Recommendations

Seeking Recommendations: I would love to get some recs from romance fans—I’m looking to read some modern works that (in your opinion) best represent the various romance genre tropes (enemies to lovers, forced proximity, love triangle, etc)

This is partly an effort to better understand an unfamiliar (to me) genre that is just massively popular (seemingly with good reason!), but I also suspect reading these works will help me refine some of the relationship dynamics in my own, non-romance novels

Dungeon Crawler Carl: If you’ve ever played an RPG (TTRPG or video game), like reading fantasy or sci-fi, or are just a big fan of page-turners with goofy humor and a lot of colorful fighting, this series is the most propulsive (in the sense of not being able to put it down, even when I should) I’ve read in a long while. The silliness and litRPG style won’t be for everyone, but for a lot of people I know who’ve picked it up (myself included), it quickly becomes a minor addiction

This series is currently burning its way through my silent reading group, and I’m halfway through book six (of seven) and am both relieved (because I have other things to read) and sorrowful (because it’s a truly fun read) about that

Some Writing (& Such) Links

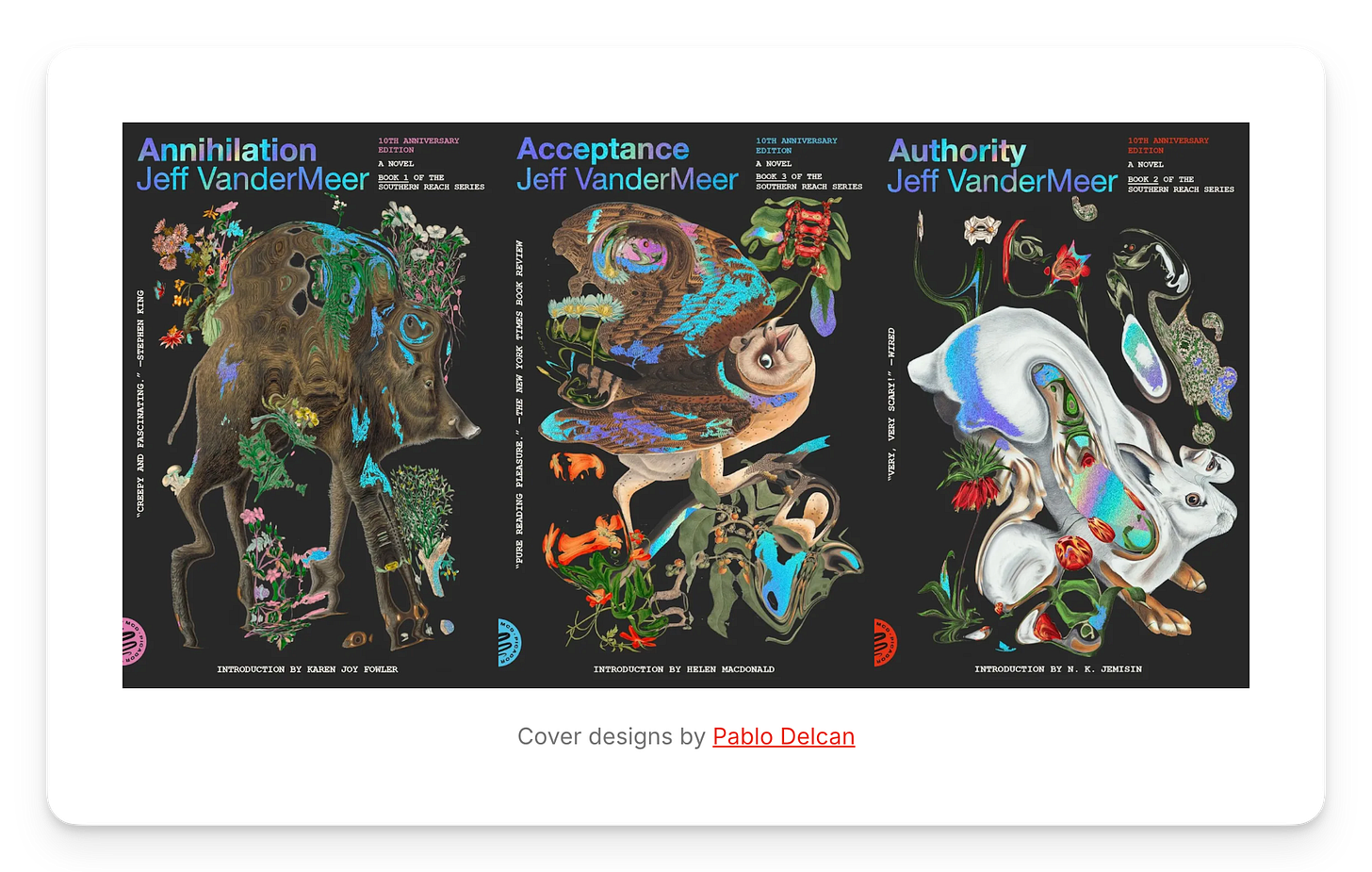

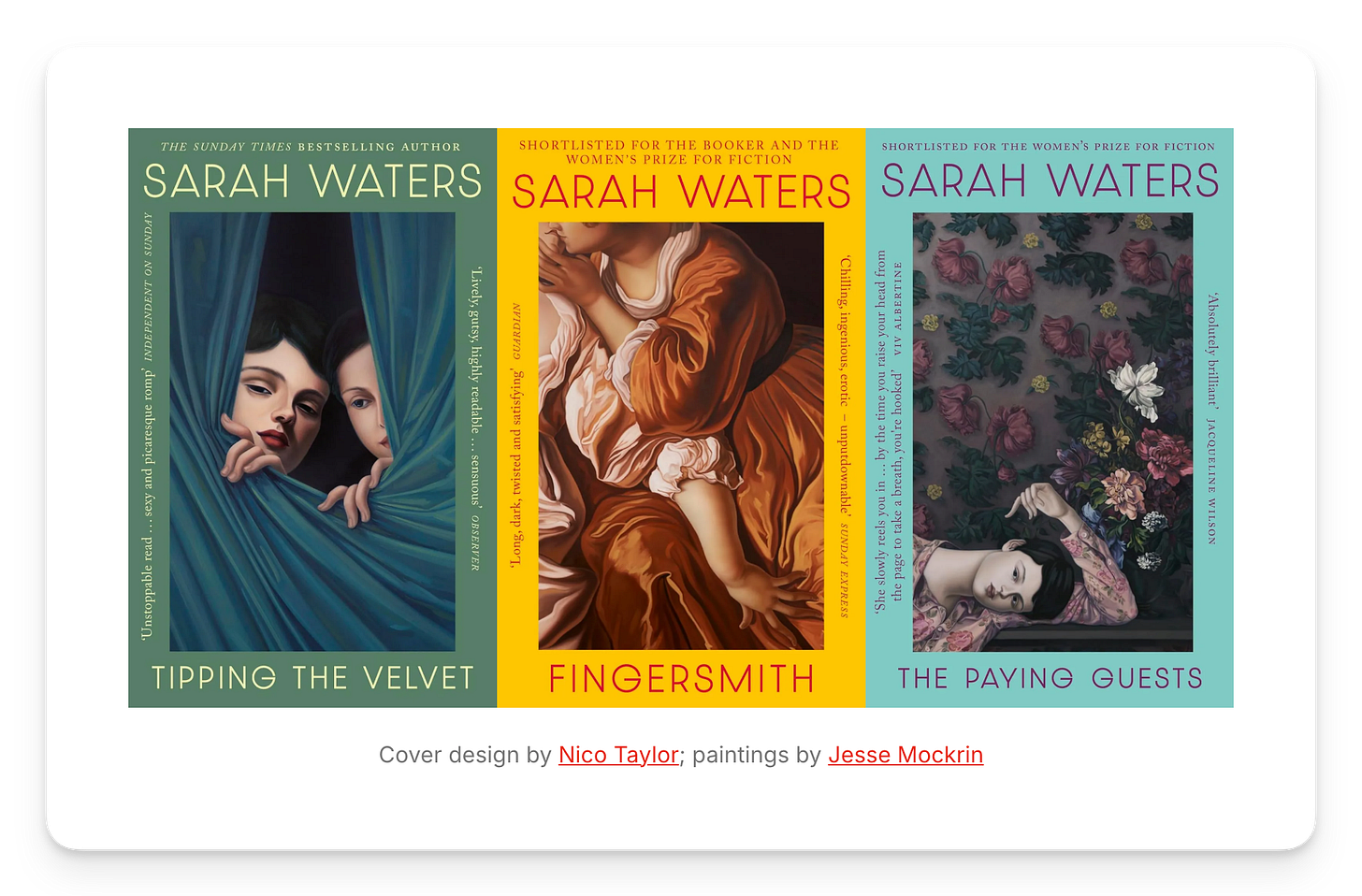

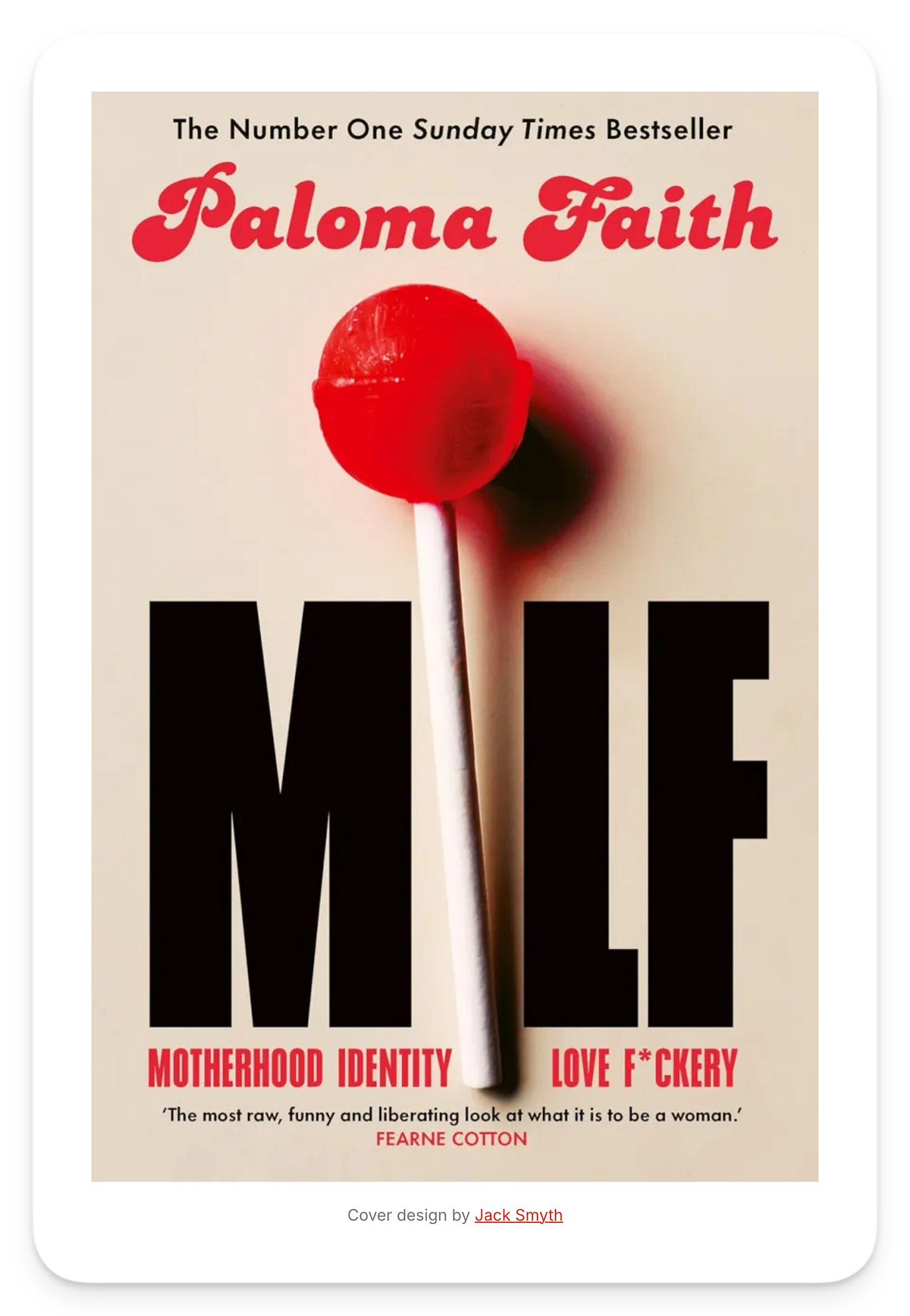

100 of the Best Book Covers of 2024

There are some absolute beauties on the list—worth a scroll all the way to the bottom

A Refuge for the Soul: How to Build a Library, According to Montaigne

From the piece: “The tower of books and the stove-heated room. No matter how much some philosophers want to disembody it, thinking always occurs in a particular time and a particular place. Socrates loved to spend time with the youth of Athens at the Agora; Plato established his Academy; Aristotle set up his Lyceum. For Epicurus it was a small garden. The Stoics got their name from the Stoa, a colonnade on the north side of the Agora. Elite Romans like Cicero, Seneca, and Pliny took great care to set up their villas with nice views, fresh air, and well-stocked libraries, which they believed to be requisites for a good life.”

The One Hundred Pages Strategy

I really like this concept/ambition, though I can also understand why it’s a bit controversial. It’s also worth noting that no approach to reading (and focusing for long periods of time, and grazing on different sorts of work, and learning in general) will work for everyone, because of our internal peculiarities, our very different lifestyles, and because of our unique reading-related priorities. But it’s worth considering a range of such approaches, because ideally we pick and choose ingredients from a bunch of recipes, eventually ending up with a dish that suits our specific tastes and needs

From the piece: “To start, then, I should say a few words about the rules, such as they are. The hundred pages strategy is not a scheme for working through reading lists. A book counts whether one is reading it for the first time or the fiftieth. Reference books such as printed dictionaries do not count unless they are being deliberately read “through” rather than consulted; the same is true of books that lend themselves to indiscriminate browsing, such as collections of essays. I also do not count books, even comparatively serious ones, read aloud to children, though I would not think it strictly contrary to the spirit of the exercise if someone else did. Otherwise there is no cheating; I do not, for example, try to guess how many pages half a dozen news stories or bits of online sports gossip would translate into. I do not count the reading of periodicals, even in print. Nor is much attention given to the size of the type. My experience suggests that this sort of thing tends to average out across authors, publishers, and editions; only poetry (which I will say more about below) will consistently throw it off. Otherwise the only outlier I can think of is the exceedingly small type of the old J. M. Dent Everymans; these pocket-sized volumes are ideal for traveling and the best way to work through very long books, such as Macaulay. In any case, one hundred pages is not meant to be a precise scientific metric; it is simply a goal, and, I think, a manageably sized one.”

Say Hello

New here? Hit reply and tell me something about what you’re writing, what you’re writing, reading, and/or about yourself!

I respond to every message I receive and would love to hear from you :)

Prefer stamps and paper? Send a letter, postcard, or some other physical communication to: Colin Wright, PO Box 11442, Milwaukee, WI 53211, USA

Or hit me up via other methods: Instagram, Threads, Twitter (ugh, but okay), or Facebook.